By Sam Pappas

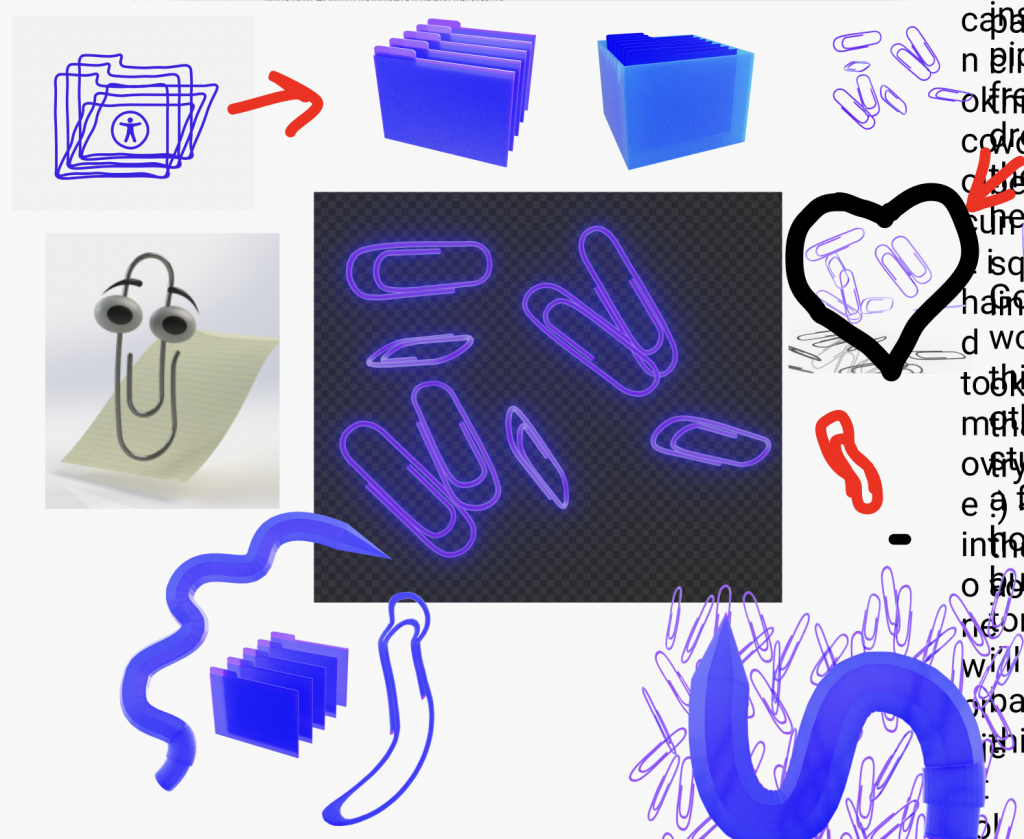

First recorded on April 3rd, 2023

In early 2021, visual artist Nat Decker (they/them) began collaborating with Gracen Brilmyer, director of the Disability Archives Lab, to create a logo representing the lab: a purple and blue paperclip, stack of folders, and pencil, each 3D and wiggling in parallel with 3D text that reads “Disability Archives Lab.” Nat is an interdisciplinary artist who works primarily with digital and sculptural mediums, using fluid shapes and bright colours to explore a crip narrative through their work and document disabled existence. In January 2023, their article “Cripping_Computer_Graphics: Perspectives on disability representation in CG via community generated 3D asset library,” co-authored with Cielo Saucedo, was published in the peer-reviewed journal First Monday [1]. The article explores the duo’s work creating the Cripping_CG project, a digital archive of 3D assets and motion capture of disabled community members.

Conducted by Sam Pappas, this interview discusses disability aesthetics, representation, crip fantasy, and collaboration as a form of disabled resistance and empowerment.

Sam Pappas: I’m excited to get to talk to you about your work both with the Lab and in general about what you’re working on. I read your article that was published this January on your Cripping_CG project with Cielo, and I’d love to pick your mind a bit. Could you tell me a bit about yourself and what led you to working with 3D technologies?

Nat Decker: Sure. I’m originally from Chicago but I’m currently based in Los Angeles, Tongva land. I’m an artist who’s largely working within disability arts. As a field, I value that it is an inherently political practice and has a lot of crossover into the type of access and mutual aid work that I’m interested in. Because of that, I’m making a lot of work about my queer disabled lived experience and trying to generate questions and provocations towards collective care. I work between digital and sculptural mediums. I’m working digitally as a form of access, to be a little less encumbered by the physicality of a traditional studio practice. But I’m working between the two and in relationship with one another.

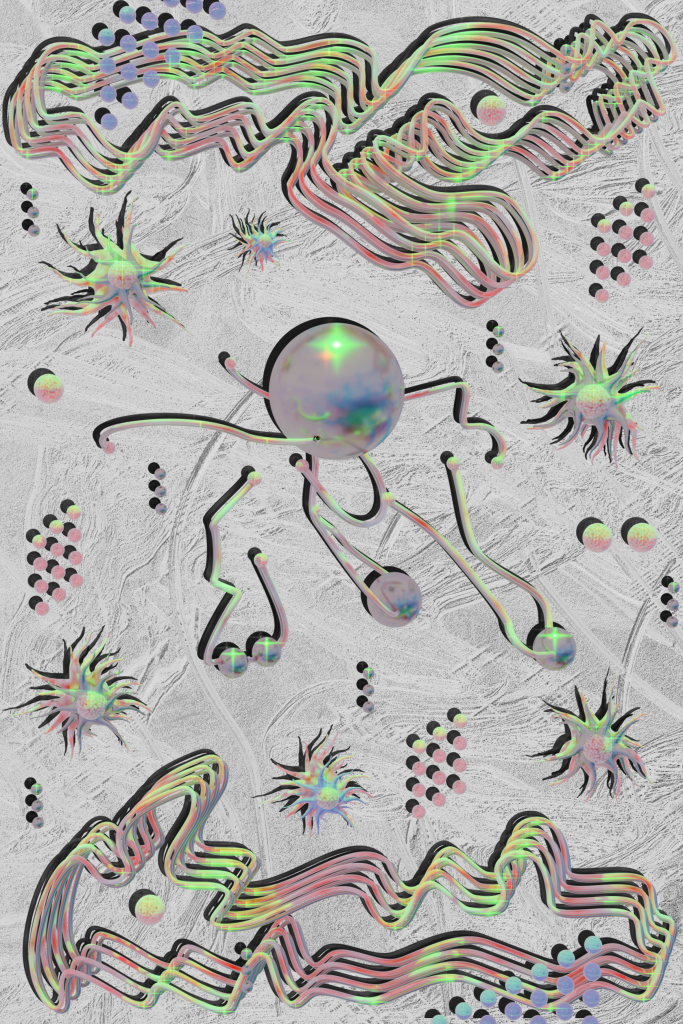

I use digital tools and sculpture to explore the mobility device as a site of crip narrative. I’m creating these reimaginings of things like wheelchairs and walkers and scooters, bringing in a lot of vibrant color and design, more organic, fluid shape. I’m trying to use those forms to embody my desires, to agitate conventions we have around desirability, the unidimensional or pitiable imaginings of disability, and, ultimately, the tools that we use for access.

You mentioned the project I’m working on with Cielo Saucedo. We’ve also brought in Olivia Dreisinger, who is now a core collaborator. We are working on our own archival project! And we’ve recently started redefining the project as a collective. We’re trying to create a platform within this particular area of research and production at the intersection of disability and computer graphics, specifically working with 3D CG modeling and animation. We research virtual digital space as a form of access, as a community space important to disability culture and the absence of disability representation within the mainstream industry. We’re exploring how mediums, such as video games and specifically within the horror genre, produce images of disability and embodiment that edge on grotesque exploitation. But also exploring forms of digital disability hacking, the ways we hack to create a self-authored presence in the space. We’re trying to collect and archive these investigations and research, and shape them into creative projects.

An important part of the project involves generating these practical digital tools that people can use for media arts, creative production. We’ve been collecting data for motion capture – which is the recording of movement, or stillness, that can be applied to computer generated models. And we’ve been making CG models of objects, making avatars, trying to collect meta-data surrounding these objects as an analysis of process and practice of consent. We’re still in early phases of this project, but we’re trying to build a web platform to house this research and these sharable tools; the digital objects that act as both a cultural archive and tools for production.

I’m also an access worker. That’s a new thing I’ve been calling myself. I still feel a little hesitant to claim the title, but I’ve been doing access consulting for arts organizations. New Art City, Creative Growth, Spoonie Collective, p5.js, a number of projects at UCLA. I graduated from UCLA as a non-traditional, older transfer student from community college in June of 2022. I studied design, media arts and disability studies. I am thinking about grad school but I’m not there yet. Trying to chill and work, and find time to make art.

SP: How did you get involved in archives and this field of art? What’s your artistic background?

ND: I was in DIY art scenes since I was a teenager in Chicago. Then I lived in Oakland for 8 years surrounded by artists, specifically the underground music scene. I became disabled while living in Oakland and had this significant restructuring of my reality and needs. I was suddenly forced to meet a lot of slowness in my life, so I had a pause. My body went through a lot of changes, but I was also fired from my museum job at the Oakland Museum of California for being disabled, lost my affordable housing, had friends disappear. I tried to frame this pause as an opportunity to make some life changes with intention and agency, so I moved to Los Angeles and applied to UCLA. I feel really lucky that I had the resources and support to experience such a pause in my life and be able to take the time to identify new paths forward. That’s not a possibility for a lot of people.

I’m grateful I was able to spend time at UCLA. It was there that I was really introduced to digital tools for art making, and the idea of a research-based, more conceptual practice. I had started getting into computers when I was working at a museum as a media specialist and was managing and repairing networked media for exhibits and digital interactives. It was my first exposure to editing lines of code and was my first deep exposure to creative software. In the Desing/Media Arts program at UCLA, I started learning 3D modeling, sculpting, and animation tools and really fell in love with the medium. It was also, importantly, work that I could create from bed, with a heat blanket around myself, during a pandemic. I was able to have access to creative tools while meeting my body’s needs. That felt meaningful. I was also excited about exploring the aesthetics of fantasy and futurity. The medium inevitably lends itself to those themes. There’s a lot of possibility with how you can manipulate and repeat form and simulate light and physics.

In this moment, many people seem very attracted to archives. They’re such an important part of cultural production and analysis. As a queer disabled artist I can recognize the ways my identity and the identity of other marginalized people, is not represented in the archives, so it is up to us to make our own. That feels like an important obligation, especially when I work with these mediums that generate so much data.

SP: How would you define the expression “disability aesthetics?”

ND: I’m still figuring this one out. I think of the early days when I was thrust into this very recognizable experience of disability, and was in the hospital and taking in the appearance of these various objects around me and these textures of sensation, objects which were so coded as medical, unwell, disabled. I started to notice their unique beauty as an act of resistance, and they became a visual language I began to relate to in my work. They became tools of building this visual world and narrative of how I was creatively interpreting, processing, and archiving what I was going through. It’s telling an intimate story. I was critiquing, but also finding deep interest in the very sterile design of these objects that related to my experience – like mobility devices, medical supplies, etc. – that were coded as disability, medicalization or illness. I’m thinking about a resistance to the “in spite of narrative”: that disabled people achieve this or that in spite of their disability. And trying to frame that around these visual symbols, that they weren’t beautiful in spite of being objects of disability, but because they were. That those symbols hold aesthetic power because they are disabled. I think a lot about the beauty of broken things.

The actual phrase was introduced to me in reading some of Tobin Siebers book, Disability Aesthetic [2]. The book is about how modern art is distinct in how it explicitly valued things that strayed from normative beauty, things that weren’t pretty, were strange, or different. There’s an interesting introduction to aesthetics being the feeling of comfort in the presence of another body or object. I considered and felt that for a long while. The book also gets into the historical canon of bodies and imagery that are representative of disability, but are either prescribed a specific attitude or not translated as disabled. Like the ways we interpret old marble sculptures that are missing limbs.

I think it’s about expansive, creative and compelling narratives, visual or otherwise, that relate to and connect somehow to the disabled bodymind or disabled experience. That can importantly explode the very finite understandings of the connotation, and the way it’s being interpreted via imagery.

SP: What is your favorite part of working on the Cripping_CG project?

ND: I love getting to work collaboratively, and on a project that is in support of the dreams and desires of disabled media artists. Disability can be such an isolating experience and as everyone has either experienced or continues to experience extreme isolation through the pandemic, it’s nice to get to work with other people on a project that’s intended to continue networking outward, but is also able to operate in a remote format. I get shy, and I don’t want it to be about me. I want it to be about community and the bigger work and shared experience.

It’s a citational practice in community with other people’s work, with long histories of work. I’m excited about leaning into that weblike network of how we experience creation as individuals within a context, to highlight and experiment with that. It’s exciting to house research that me and my collaborators are interested in, and how we can collectively share our skills and our areas of interest. And I really do enjoy working with these tools. Sometimes they’re very tricky. We had some illuminating but frustrating barriers in working with the motion capture equipment that was available to us. But it can feel so generative when you do meet those moments where the tools are resisting, or the tools aren’t working for us. It feels vital to be able to identify those moments and call them out, and try to therefore create more space for the tools to improve and change. Well, maybe they won’t. Maybe they will. But it feels like an important obligation.

SP: You mentioned there were other equipment options, but they were all incredibly expensive. It seems like even then you can’t guarantee that they will work with all bodies, all assistive equipment. It’s frustrating, but important to identify that frustration and hopefully find other ways to work around it.

ND: Yeah. There’s never gonna be perfect access. And it’s possible these tools are in conflict with how a person might want to experience representation of their disabled bodymind. The equipment and medium presents numerous access barriers, and the industry it is bound to is very neoliberal hyper-capitalism. But we have found value and interest in this technology, and we’re all trying to constantly push towards better access. There are a lot of fundamental access issues in this field around costs, availability, and access to computational tools. The project is about creating opportunities for other artists to be able to work with some of these tools, but there are a lot of barriers.

It’s frustrating because disabled people feel like they’re screaming into the void a lot of the time. With this very, very fast-moving tech industry, that acceleration does often leave behind some of the more nuanced needs of tools to meet the most widely profitable, deliverable, model. There’s a lot about the hyper-growth cycle that is in friction with my own needs and desires around slowness. It’s important that people working with technology are critical, especially of the capital and market driven side. But it’s also about hacking and how we can find ways to make these tools work for us, build our own tools, or modify tools to work for us. And that’s meeting a long history of disability hacking, which is important. But we’re really trying to get access to some of those tools, trying to apply for funding. It’s tough. Sometimes I do get a little dejected, wondering when we’ll be able to bring the project further along, because we also meet those barriers.

SP: When did you design the Disability Archives Lab logo? I know it was a collaborative process with Gracen – about how long did it take?

ND: I don’t know. I remember I was struggling to keep up with work and school. It’s interesting how even when you’re working with somebody you can trust and somebody who intimately understands crip time, you can still feel a lot of shame around that. I know I kept asking for a little more time from Gracen, and I was worried it would be frustrating. But Gracen was so gracious and so sweet, so it was a really fun process. Very collaborative. I want to say it was maybe early during winter, early 2021; it was deep pandemic.

Gracen told me some of the motifs they were interested in being included. Then it was back and forth doing some modeling, some tweaks and edits, getting feedback. It was fun. I was just starting to get into 3D software so it was a learning process. I love a project that allows me to learn skills as I go. And you know, I like a little wavy organic form, I like a little squiggle. It’s about wanting to explore difference, instead of normativity and rigidity of form.

I think in our conversation, the warped shape was wanting to exemplify something that is warped and different from our rigid ideas of what a bodymind is, what an archive is. Leaning into that. I think that speaks a lot to disability aesthetics in general, wanting to really find something significant and beautiful in form and shapes that are other, that are warped from our base concepts of what a body or thing is. Gracen wanted a pencil and a folder and a paper clip so I modeled those, which was really fun to do.

And then Gracen had chosen that bright purple blue color which I coincidentally work with a lot. I know Gracen had wanted something that would work on both dark and light mode on a browser, which I was into. More access, more designing with flexibility and versatility in mind. So we made sure it was something that would work with a dark background as well.

SP: Are you currently working on any other projects that you’re excited about?

ND: I’m making some changes to have more space for art by trying to be realistic about how much energy I can devote to my work vs. money work, finding ways to pay my rent, studio rent, and buy the cat the fancy food. Dealing with the fear and tedium and insecurity. I’ve started freelancing and working half-time at my job, but I’m excited to get some things a little settled, and then dedicate more time to thinking about what some of my next artistic projects will be. I feel like I’ve been in application season. A lot of writing about the work I want to be making, and then not actually having the energy reserved to go to the studio.

I have some plans for more physical work. I’m excited to really dedicate time to get oriented on some of the underlying concepts, which will continue to be about things like crip futurity, technology, hacking, desirability, and disability aesthetics. I’ll try to do some writing and reading, dig deeper into some ideas, make work.

But I’m excited. I’m going to be at a residency at a print lab called Latitude in my hometown in Chicago for all of June. I’ll receive some good structure and pressure to be producing. I’ll also be going back to ACRE in July, another residency. Hopefully other things.

SP: Is there anything else you wanted to share for this interview? Any further collaboration planned with the Disability Archives Lab at this point?

ND: I would love to have more collaborations with the Lab and with Gracen. I know we were previously talking about disability and AI, and I have been doing some research on that. Then I was too busy, being a student is so hard. It’ll be hot out soon. I also want to go swimming. I think that’s a collaboration. I feel like everything I do in life, which is inevitably with support from my friends and community, is in collaboration. But I just want to have some fun, eat some good food. I want to read a lot of books this summer. Get some sunshine and just laugh a lot.

About the Authors

Nat Decker (they/them) is a Chicago born Los Angeles based artist interpreting the intimacies of queer and disabled lived experience as provocation toward collective care and liberation. Operatively creating between digital and material mediums, they identify the computer as an assistive tool affording a more accessible practice. Often from bed, they use digital 3D software to trace serpentine connections between the body and technology, reimagining fantastical mobility devices as cultural celebration and agitation of conventional desirability politics. This cyclically informs their work with sculpture, creating non-functional mobility devices as aesthetic scrutiny and frictional commentary on designations of usefulness. Nat is also an access worker, consulting on accessibility for organizations such as p5.js, New Art City, Creative Growth, the LA Spoonie Collective, and for various projects at the University of California, Los Angeles. In June 2022 they graduated from UCLA with a degree in Design/Media Arts and Disability Studies.

Sam Pappas (he/she) is a Research Assistant for the Disability Archives Lab who is graduating this June with a Master’s of Information Studies from McGill University. He is interested in identifying and deconstructing systemic barriers to information, and the role of community-run information organizations. Sam is a white, chronically ill, autistic, butch gender non-conforming lesbian.

Bibliography

- Saucedo, Cielo, and Nat Decker. “Cripping_Computer_Graphics: Perspectives on Disability Representation in CG via Community Generated 3D Asset Library.” First Monday, January 16, 2023. Link to open access article “Cripping_Computer_Graphics”

- Siebers, Tobin Anthony. Disability Aesthetics. Illustrated edition. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010.